Crash Team Racing AI

Problem definition

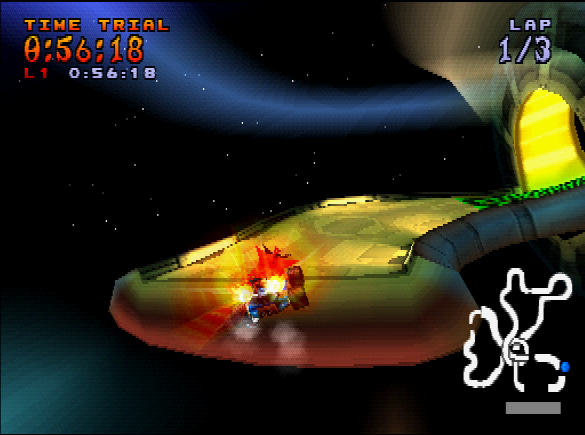

In this project we aim at creating an AI able to play Crash Team Racing in Time Trial mode.

The AI will not be provided with any game state information like kart position or speed; nonetheless, we allow it to infer such information by looking at the raw pixel data.

The GIF shows an example of Crash driving through Coco Park track. Numbers show - frame by frame - the AI’s propension to steer left, continue forward or steer right, respectively.

In this project we aim at creating an AI able to play Crash Team Racing in Time Trial mode.

The AI will not be provided with any game state information like kart position or speed; nonetheless, we allow it to infer such information by looking at the raw pixel data.

The GIF shows an example of Crash driving through Coco Park track. Numbers show - frame by frame - the AI’s propension to steer left, continue forward or steer right, respectively.

If you are not interested in reading a description of this project, but only in using the model, please jump to the “User guide” section at the bottom of this page. User guide

Data

The data creation process consisted of recording several minutes of human gameplay (shout-out to my friend Nick for his help). Every frame is captured from the emulator by OpenCV, rescaled to a 160x90 RGB image and then converted into a numpy object. In addition, every numpy object is paired with a value representing what key was pressed by the human racer in that precise instant. We have decided to force a frame rate of 10 FPS in order to avoid storing too similar images.

All of this will help the AI to learn a correct steering behaviour with respect to the image seen by the driver. For example, when there is a right turn and the kart is positioned on the left side of the street, the AI will often prefer steering right since it has seen that behaviour in similar scenarios within the training dataset.

At this stage, data was gathered for one track only: Coco Park. However, it would be beneficial to have captures spanning across multiple tracks; perhaps leaving outside one or two of them so that we could test how well the model is able to generalize in different environments. N.B. CTR tracks have very different layouts: there are sewers, canyons, castles and even an orbital space station!

Data analysis

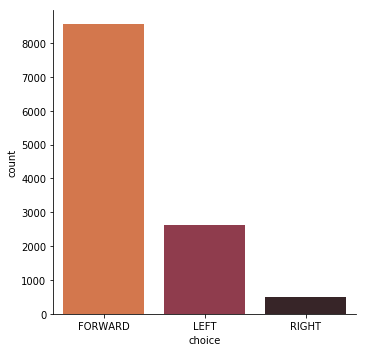

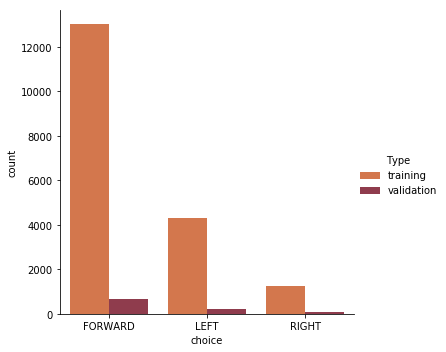

When the initial data collection is over, we can plot a distribution for the different possible choices.

The graph clearly shows that the dataset is unbalanced, a common problem in machine learning. Most observations - as one could expect - have forward as the correct choice, followed by left.

Feeding this data into a neural network will most likely end up with the model always predicting forward as correct choice, since that would still have a very high accuracy given how unbalanced the dataset is.

Researchers have proposed several techniques to tackle such problem and, after reading the NVIDIA self-driving cars paper [1], we have opted for oversampling. Data collection is extremely cheap for this problem and it justifies such choice.

In this specific case, we drive intentionally to a wall or on the grass, start a recording section where we adjust our position and repeat this process until we have a good number of recovery observations.

When the initial data collection is over, we can plot a distribution for the different possible choices.

The graph clearly shows that the dataset is unbalanced, a common problem in machine learning. Most observations - as one could expect - have forward as the correct choice, followed by left.

Feeding this data into a neural network will most likely end up with the model always predicting forward as correct choice, since that would still have a very high accuracy given how unbalanced the dataset is.

Researchers have proposed several techniques to tackle such problem and, after reading the NVIDIA self-driving cars paper [1], we have opted for oversampling. Data collection is extremely cheap for this problem and it justifies such choice.

In this specific case, we drive intentionally to a wall or on the grass, start a recording section where we adjust our position and repeat this process until we have a good number of recovery observations.

A preliminary AI was built with the use of the initial dataset. Results showed that the AI had issues navigating through the dark section of Coco Park, and that it was steering towards the pink pillars present throughout the map. Similarly to what done with recovery data, we have improved our dataset further by collecting additional minutes of driving in these areas where the AI was performing poorly. Finally, the latest dataset was randomly split into a training and validation set with a 95/5 proportion.

Model

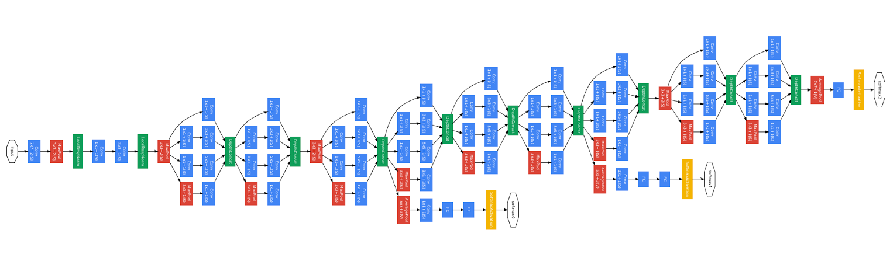

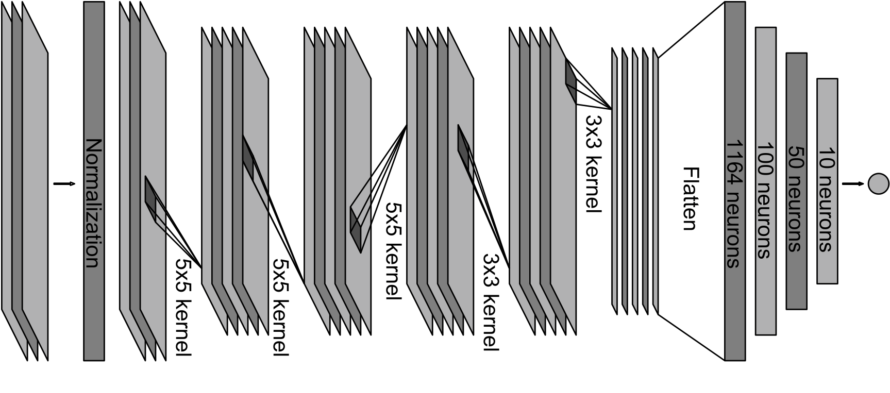

After some research, we have found two model architectures that have already been applied successfully to similar problems. The first model is Inception (GoogLeNet), which was originally designed for the ImageNet Large-Scale Visual Recognition Challenge in 2014 [2], and recently used by Sentdex to train an AI to self-drive a car in Grand Theft Auto V [3]. The second model was developed and implemented by NVIDIA to show an end-to-end process regarding self-driving cars. Both models are convolutional neural networks and a version of their architecture is shown in the two pictures below.

Our implementation in Tensorflow (specifically, TFLearn) follows the overall architecture of Inception and NVIDIA model, but there is a key difference: our two models do not predict a steering angle, but simply a direction, i.e. left, forward, right. The reason for this is that Crash Team Racing does not allow us to input a coordinate, but only what key is pressed on the D-PAD (remember that this game was released in 1999).

Training

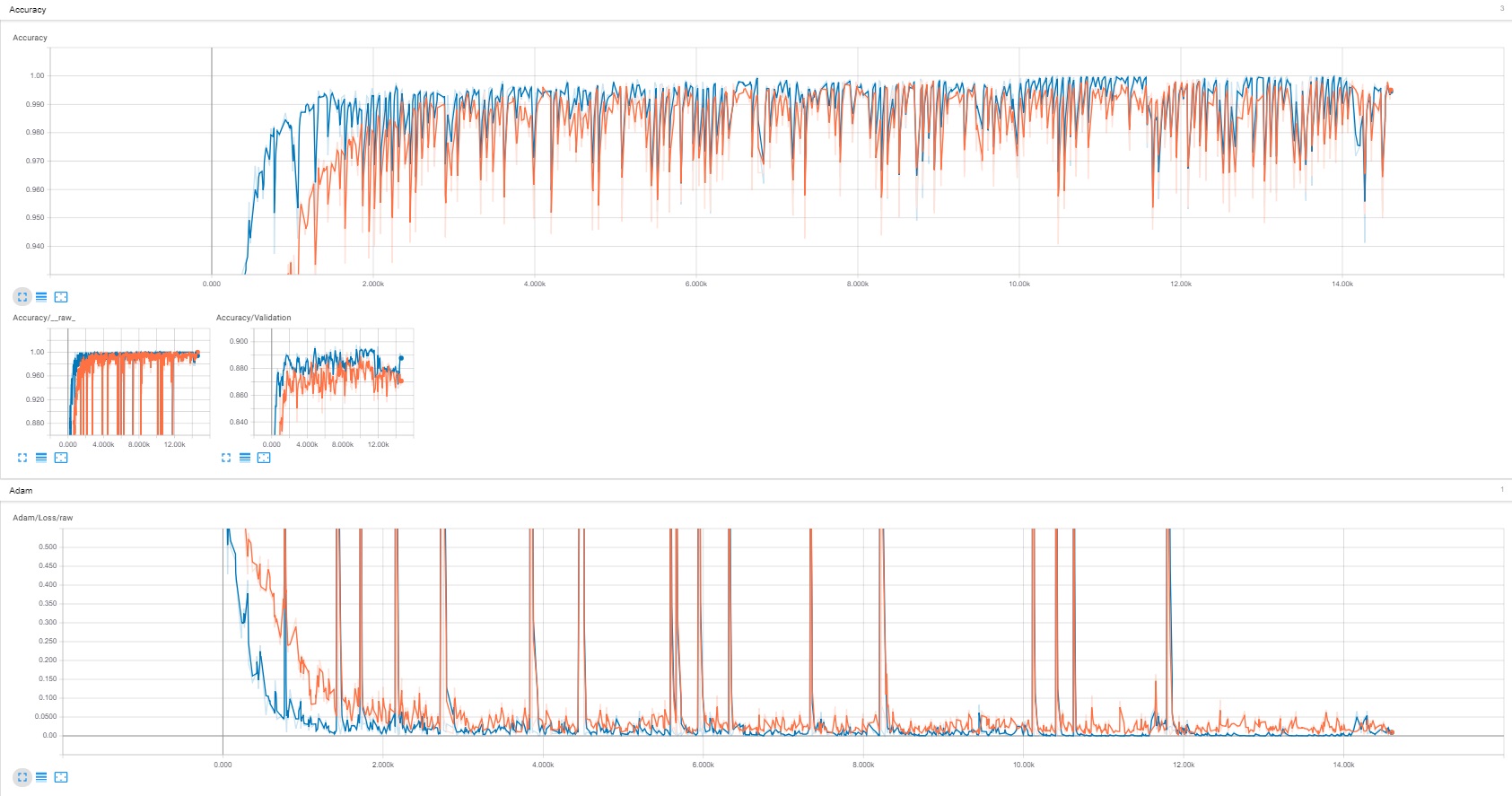

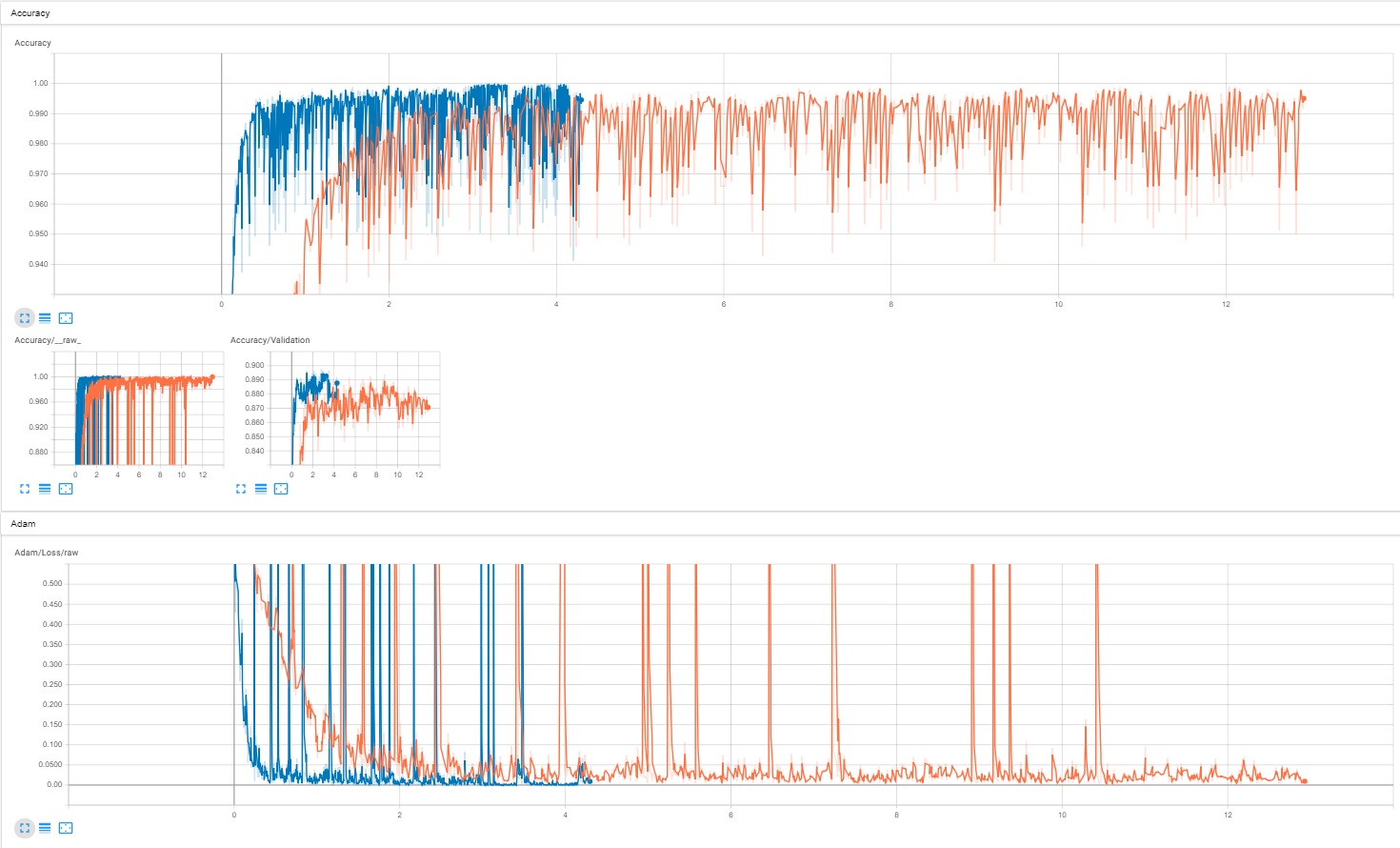

We have tried different optimization methods and the best performing was Adam optimizer. Learning rate was set to follow a simulated annealing decaying schedule, i.e. the learning rate is reduced over time. Regarding the batch size, we initially opted for 512 but then moved to 256 because of memory issues.

Models were trained on a GTX1080 Ti, without the use of transfer learning. NVIDIA model was much faster to train (200 epochs in ~4 hours) than GoogLeNet (200 epochs in ~14 hours) and it had overall better performance, especially for the first ~30 epochs. However, when both GoogLeNet and the NVIDIA model are trained for a longer period, performance is similar.

As shown in Tensorboard screenshots above, the final versions (NVIDIA = blue, GoogLeNet = orange) were able to achieve 99.5% accuracy on training data, 89% on validation data and had a cross entropy loss close to 0. More importantly, they can drive on Coco Park track with great results.

Deployment

After the model is ready (regardless of which version we choose) we need some additional steps to have a production version for the self-driving Go-Kart. First of all, while the game is running we must pass an image that fits the model requirements. This is done in a similar fashion to the data creation process: OpenCV reads the frame, rescales it and passes it to the CNN model in real time. Then, the model outputs one prediction for each possible move (left, forward, right). On top of this prediction, we have tried two simple logics to pick the actual choice:

- argmax selection

- weighted random selection

Argmax selects the move with the highest prediction value; however, a weighted random selection seems to perform better in this context. For example, if the “raw prediction” is 0.4 left, 0.5 forward and 0.1 right, we will decide to turn left, continue straight or turn right following the respective probabilities. This selection is performed at every detected frame and the noise brought in by the weighted random does not show any relevant stuttering with the driving behaviour. On the contrary, argmax tends to get stuck when it hits a wall because in unclear situations, it ends up constantly selecting forward. For Crash Team Racing, we have the gas button (forward move) always pressed since a good driver - human or bot - is capable of navigating through the different tracks without a need for deceleration. This decision is specific to CTR and we do not suggest to apply the same logic in different games.

Directional inputs are passed to the game through a virtual keyboard, thanks to the snippet shared by the stackoverflow user hodka [4].

Results

As a final test, we compared the lap times obtained by GoogLeNet, NVIDIA and an expert human player over 5 races. This is by no mean statistically significant, but should at least give an idea about the possible performance and areas of improvement. The table below shows lap times in seconds; an asterisk (*) means that the kart drove to a wall or on the grass - causing a considerable time waste. Please note that we do not allow power sliding, a technique that allows Crash to drive faster than the standard speed by using a specific combination of inputs.

| NVIDIA Lap 1 | Inception Lap 1 | Human Lap 1 | NVIDIA Lap 2 | Inception Lap 2 | Human Lap 2 | NVIDIA Lap 3 | Inception Lap 3 | Human Lap 3 | NVIDIA Total | Inception Total | Human Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 152.36* | 40.94 | 38.35 | Incomplete | 44.79* | 37.29 | Incomplete | 41.98 | 37.10 | Incomplete | 127.71 | 112.74 |

| 41.77 | 46.19* | 38.38 | 48.19* | 41.37 | 37.30 | 46.67* | 85.96* | 37.26 | 136.63* | 173.52* | 112.94 |

| 40.49 | 43.00 | 38.51 | 42.5 | 41.73 | 37.49 | 122.00 | 42.15 | 37.27 | 204.99* | 126.88 | 113.27 |

| 50.18* | 42.60 | 38.38 | 45.74 | 41.16 | 37.36 | Incomplete | 39.76 | 37.28 | 95.92* | 123.52 | 113.02 |

| 75.68 | 42.24 | 38.01 | 66.47* | 40.41 | 37.33 | Incomplete | 41.12 | 37.20 | Incomplete | 123.77 | 112.54 |

As expected, none of the models is able to outperform an expert human player. Nevertheless, GoogLeNet was just 10 to 15 seconds slower in 4 out of 5 races. This is partly justified by the fact that the driving style during the data collection phase was much more “relaxed” than the one used for performance measurement.

Results for the NVIDIA model were slightly disappointing. The metrics shown by tensorboard pointed to this model as the best one; however, during the testing phase it would often drive to a wall. Then, it would try to escape by driving in the opposite direction, resulting in a large “WRONG WAY” message popping up on the screen, which the AI is unfortunately unable to understand. By looking at the replays we noticed that the NVIDIA model constantly gets stuck in the exact same wall through the dark tunnel, suggesting that some more data would be useful for that section of the track. Beside this problem, the NVIDIA model’s driving skills are comparable to GoogLeNet’s.

Conclusion and future improvements

This project shows yet another example of how videogames can be used as simulations for real life applications like self driving transportation. CTR-AI displayed great results but it still has room for improvement - especially when considering that it was built with a proof of concept mentality, more than finished product.

The first improvement to take care of would be to collect a larger amount of data. For a neural network, driving is a complex task and it is impressive how good the test drive performance was, if compared to how little data points were available. At this stage, GoogLeNet model can drive in a way so similar to humans that we are considering to automate the data collection by having the AI run autonomously and storing only runs below a certain time threshold. This would bring some difficulties because, as mentioned in the introduction, we do not allow the AI to read the game state. A possible solution is to use Optical Character Recognition to read the time elapsed directly from the pixels data.

Another simple but necessary enhancement is to extend the dataset to other tracks. Coco Park was chosen since it is the most realistic scenery in CTR’s world; however, there are many other interesting tracks. After some research, we found an AI that was trained on multiple tracks of Mario Kart game, confirming our assumption that it is indeed possible. Kevin Hughes’ project is great and we definitely suggest to have a look at his Github page [5].

Finally, we are currently working on making CTR-AI capable of playing other modes such as Arcade. In Arcade Mode Crash races against other opponents and has access to a set of weapons that can be used to slow down or disrupt other players. This means that the AI has to learn new tasks such as: to understand if a weapon is available and which one it is, to use weapons in the correct way and perhaps to detect enemies’ location to optimize the attack strategy.

In conclusion we are satisfied with the results and hope that you will test out the code with your own gameplay. For doing so, please refer to the User guide section.

User guide

Here we describe how to replicate the entire study; however, you can opt to use the already trained model by only following steps “Dependencies” and “How to run the model”. We only share the Inception model, due to the models weights size.

Please, notice that many files have hard-coded folder locations since we used two different hard-drives to store code and all the data/models.

Dependencies

Install all the necessary dependencies listed in the requirements file.

pip install -r requirements.txt

How to collect and validate dataset

For this and the following steps you need to have a PC version of CTR; we suggest running the game with a 4:3 resolution ratio. To start creating your own dataset, change the output folder path in collect_data.py and run it. The script will start recording your gameplay and store the clips.

Here is an example of user D, driving through coco park track in normal mode (file label=N):

python collect_data.py D coco N

After recording a session, we suggest to validate the data with the help of visualize_test_data.py:

python visualize_test_data.py file_name

When you are satisfied about the amount of recordings collected, use merge_training_data.py to gather all data into one file (remember to change the path).

python merge_training_data.py

How to train the model

To train the model, simply use train_model.py. We suggest to keep the hyperparameters untouched, since they have shown good results. The script automatically takes care of splitting the dataset into train and validation; change VAL_PERC to use a different proportion between the two sets.

This file uses Nvidia model by default, but you will also find the Google’s version commented out. As always, update the folder location with the correct path.

python train_model.py

How to run the model

To run the model, use test_model.py. The default values will load Inception model, but you can also pass your own customized model.

python test_model.py

References

[1] End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars

[2] Going deeper with convolutions

[4] Simulate Python keypresses for controlling a game

[5] TensorKart